Genna Sosonko: Russian Silhouettes

Review of the chess book

by Prof. Nagesh Havanur, May 2004

first published in Chess Mate, the monthly chess magazine from India

Genna Sosonko: Russian SilhouettesReview of the chess book

by Prof. Nagesh Havanur, May 2004 |

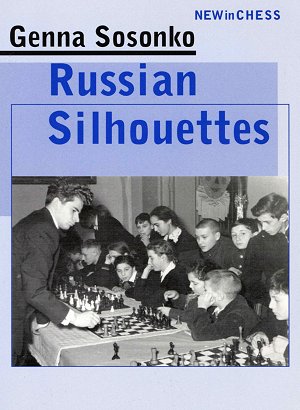

Genna Sosonko: Russian Silhouettes

Published By New In Chess

$23.95, 21 EUR

Russian Silhouettes is a nostalgic tribute to a vanished world. The lives of almost all the characters in the book belong to the Soviet Era. Genna Sosonko presents an array of memorable figures like Tal, Botvinnik, Geller and others. He was personally acquainted with most of them, Levenfish being the lone exception.

For the aspiring player there is no greater inspiration than reading this book even though it has no games.

The most extraordinary portrait here belongs to Tal. Here is Sosonko on the other-wordly character of the Latvian genius:

He was as from another planet …He belonged to that rare category of people, who, as if it were something that went without saying, rejected everything to which the majority aim, and went through life with an easy step, a chosen one of fate, an adornment of the earth. In burning out his life, he knew that this was no dress rehearsal, and that there would not be another one. But he did not want to and could not live in any other way.

Then there is the moving account of Tal's relationship with Koblenz, his trainer from childhood.

Koblenz always remained for Tal the beloved Maestro, and Tal for him was Mishenka, beginning from the moment when he first saw him as a little boy in 1948, even to the final moments in June 1992, when tears welling up in his eyes kept him from uttering the final words of parting at Tal's funeral.

Death casts its dark shadow over each of the characters in this book. Sosonko recounts the last days of Botvinnik:

…then one day he fell ill, and was taken to hospital, which he positively disliked …Pleurisy was diagnosed …and he got worse. But even in this condition he remained Botvinnik. He told the doctors which preparations were needed to neutralize the reaction. All the conditions in his organism began to develop and the ultimate cause of his death was cancer of the pancreas . He died bravely, realizing perfectly well that he was dying, with a clear mind and a firm memory.

He was calm to the very end, deliberately accepting the formula of the ancients: it is easier for us to be very patient, there where it is not in our power to change anything. Few can say when they are dying: 'I lived in the way I considered right.' I think that he could have said this .

He was at home surrounded by his loved ones, and with undiminished clarity of mind he gave the final directions about the morgue, the cremation, and stressed the pointlessness of splendid funerals .

While one admires Botvinnik's philosophical calm and detachment it should be remembered that others were not as fortunate. Zak, the famous coach of Spassky and Korchnoi, had to move into an old men's home.

It is not in the traditions of Russia to move old people out of their family into an old persons' refuge. Those who live there are usually they who no longer have any one. He was lonely and miserable. He escaped from there several times, his absence was noticed, a search party was sent out, and he was brought back. Where was he going? Home? To his pupils? To his distant Berdichev childhood? Vladimir Grigoryevich Zak died on 25 November 1994.

The fate of Levenfish, a brilliant imaginative player, was even more tragic. He began his career in the Tsarist Era and played with the likes of Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine and Rubinstein. He was one of the leading Russian masters during the 1920s and 1930s. But after the rise of Botvinnik he was ignored by the official establishment. Levenfish was a man of integrity and independence. He was not allowed to go abroad and participate in international tournaments like AVRO 1938, even though he had won the USSR Championship. This led to his gradual retirement from active play.

He was the only Soviet grandmaster not to receive a stipend. He lived in great poverty in a room with firewood heating in a communal flat. He was very hard up, but he never complained to anyone about anything.

In 1961 Boris Spassky was playing in the USSR Championship. In one of the last days of January in the Moscow subway he saw Levenfish: Aged, pale, like an apparition, he was walking along holding his head in his hands.

'I have had six teeth removed' was all he could say. A few days later Grigory Yakovlevich Levenfish died .

Levenfish was the mentor of Smyslov and co-authored a classic work on Rook Endings with the former World Champion. Smyslov remembers:

In his last few years he came to me with a stack of paper, the manuscript of his book on rook endings, and asked me to check it …I checked his analysis and made corrections in places, but it was he who did al the hard work. To this day it gnaws my heart that I was not at his funeral. I had an adjourned game, I think it was with Khasin, and it was resumed on the day of the funeral ... I tried everything to win it, but I didn't win it, of course. See what human vanity leads to ...

His artistry and deep understanding of the game are still recalled by veterans like Bronstein and Korchnoi who were fortunate enough to know him when they were young. Korchnoi makes a special mention of the game in which he was on the receiving end against the 64-year-old master. The same is being presented for our visitors:

|

Korchnoi - Levenfish [E07]

|

What brings the characters in Sosonko's book together is their love for chess. Yet there is a kind of spiritual divide between them. Players like Botvinnik, Levenfish, Furman, Geller and Polugaevsky were men of discipline and determination. It was these qualities that provided coherence and purpose to their vocation. Besides, they had a sense of proportion in life and retained their sanity.

For others like Vitolins and Grigorian chess became a consuming passion. It devoured their souls. The quest for fantasy snapped all links with reality. Each embraced death, for nothing else was left. Sosonko's essay "The Jump" is a meditation on the ephemeral nature of all things and transience of life. The only winner in the Final Endgame is Death. It snuffs out life, but spares art from extinction. Let us be grateful for those small mercies.

Warmly Recommended!